Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park is a hidden gem in Phillips, WI. Nestled in Wisconsin’s Northwoods, Phillips is a charming city and the county seat of Price County. Located along Highway 13 and north of Highway 8, this unique attraction is a must-see.

If you’ve never been to the Concrete Park or even heard of it, you’re in for a treat, and I’m thrilled to tell you all about it. I vividly remember the first time I stumbled upon it. My friend and I were driving along when suddenly, we saw this park filled with large human and animal sculptures on the side of the road. I couldn’t believe my eyes and shouted to my friend, "Did you see that?!" Without hesitation, I turned the car around, eager to investigate what we had just discovered.

But let’s start with the man behind these cool yet somewhat spooky statues: Fred Smith.

Who was Fred Smith?

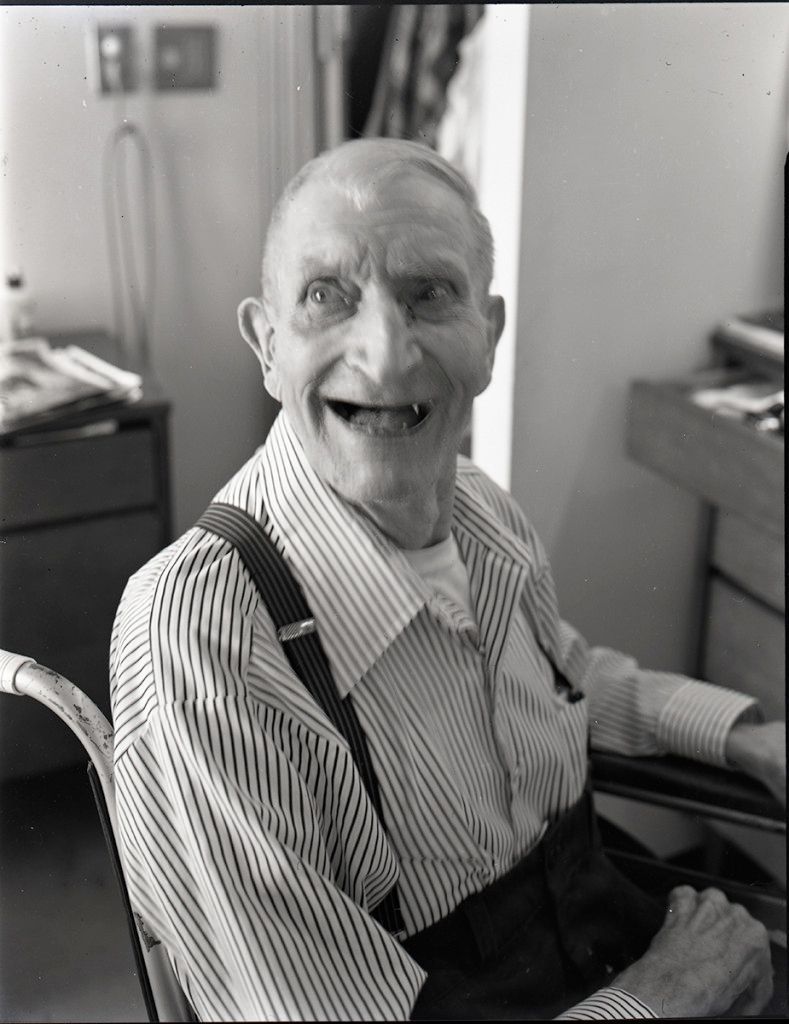

Born on September 20, 1886, to German immigrant parents in Ogema, Wisconsin, about 20 miles south of Phillips, Fred had an extraordinary life. Despite having no formal schooling and being unable to read or write, Fred was an avid musician who loved to entertain with his fiddle and mandolin. Music played a vital role in his life, from childhood into old age. Remarkably, he made his first fiddle at the age of twelve using a cigar box and horsehair. Fred was known for breaking out his instruments in his tavern, where he would play and entertain both locals and visitors. His music was a cherished part of the community, and his legacy lives on through a record of his songs, which is preserved at the museum. You can even listen to these tracks on the Wisconsin Concrete Park website, offering a glimpse into the vibrant musical life of Fred Smith.

Later in life, when asked if his illiteracy had ever hindered him, Fred confidently replied, "Hell no, I can do things other people can’t do!"

Smith began working in lumber camps near Spirit, Wisconsin, in his early teens. For just 99 cents per day, he would rise at the crack of dawn and labor until darkness fell, enduring the frigid Wisconsin winters. He worked with large horses and massive, hand-operated logging tools to cut and transport giant pines.

Reflecting on those times, he said, "I made just that little bit of money and lived 5 kids and a woman on that money. Never made no debts, never! That goes to show what people can do!"

The land that now hosts the Wisconsin Concrete Park was part of the massive lumber clear-out during the late 1800s, leaving it completely barren. In 1903, at just 17 years old, Fred Smith purchased 120 acres of this land. Here, he built his homestead with his wife, Alta. Though details about their meeting and marriage remain elusive, Fred and Alta spent their entire married life on this land, raising their five children.

On his homestead, Fred grew ginseng, which he sold to marketers in New York, and raised Christmas trees that he sold locally during the holidays.

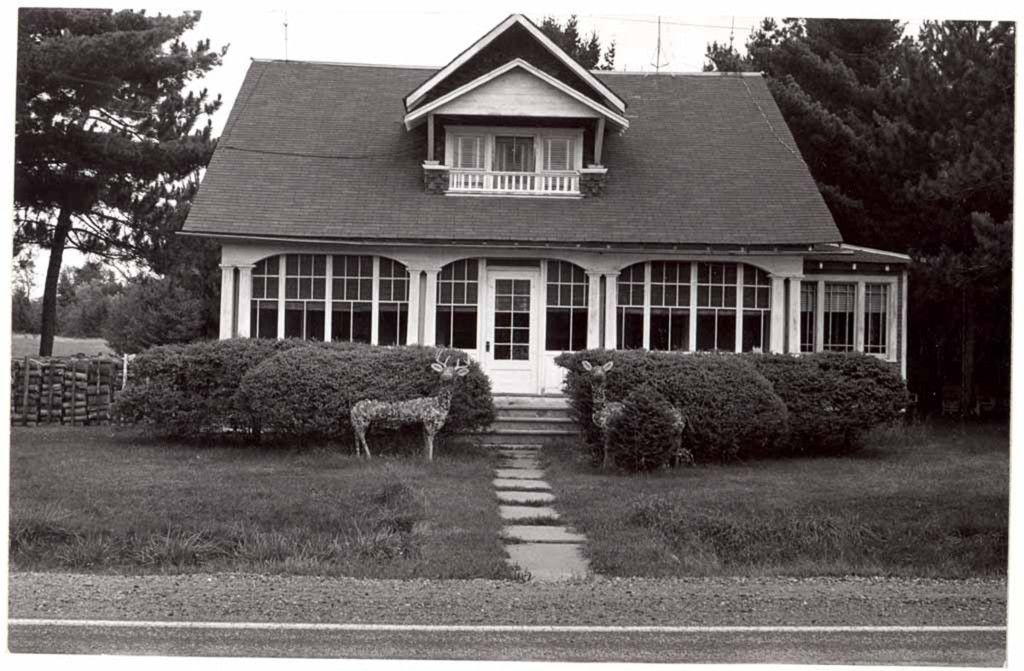

The original Smith house burned down in 1922, and it was replaced with a sturdy, Craftsman-style house that may have been ordered from Sears and Roebuck. If you didn't know, mail-order homes could be purchased through catalogs from as early as 1906 to as late as 1982. Buyers would receive both the architectural plans and all the materials needed to build the home.

How did it work? You would mail in your order, and Sears would collect all the pieces and ship them via train car to your location. Imagine receiving everything you needed to construct a home—lumber, nails, shingles, doors, and windows—delivered to your property. You'd then follow the plans and assemble your house from the ground up. It was an innovative and affordable way for many Americans to achieve the dream of homeownership, and the Smiths were among those who took advantage of this opportunity to rebuild their lives after the fire.

Out of curiosity, I looked up what a Sears catalog Craftsman home would have cost in the 1920s when the Smiths would have rebuilt their home. Back then, the starting price for a house from Sears, Roebuck & Company was only $659. That's the equivalent of $16,164.74 today.

Keep in mind, this price covered just the materials needed to build the house—you'd still have to assemble it yourself. Can you imagine paying only $659 for all the building materials for your home? What a wild thought! Today, that kind of money might not even cover a few months of rent, let alone an entire house worth of construction materials. It really puts into perspective how much times have changed.

In their new home, Smith transformed the south-facing sun porch into a lush Rock Garden Room for Alta. This serene space featured a long brick trough filled with a carefully curated rock garden, complete with a tranquil fountain and an array of living plants surrounded by collected stones accumulated over the years.

Remarkably, this unique feature is still intact today. When you visit the old home, now repurposed as a gift shop, you can view this original creation firsthand on the porch.

Right outside the porch, Fred created his own elaborate Rock Garden, which would later evolve into the renowned Rock Garden Tavern. Originally built in 1936, the tavern was a testament to Smith's artistic vision, featuring his unique sculptures integrated into its structural elements. Assisting him were the skilled Raskie brothers, known for their craftsmanship in using fieldstone and distinctive tinted, rope-style mortar joints in building impressive stone structures throughout the area. Alongside Fred, they collaborated on the tavern's construction, with Fred innovatively crafting homemade concrete blocks for an addition to the tavern.

Reflecting on those days, Fred fondly recalled, "I just had Rhinelander beer. Only one beer! I bought a truckload of beer every time we went to Rhinelander. 200 cases every time."

Around 1948, Fred Smith decided to retire from his work in the lumber camps, a decision often attributed to severe arthritis. However, retirement didn't mark an end to his days of intense labor; instead, it sparked a new phase of creativity. Over the next 15 years, Smith embarked on an ambitious project, transforming the land around his home and the surroundings of his tavern into his personal studio.

Smith's artistic endeavors were undoubtedly influenced by the larger-than-life scale of lumber work, famously depicted in the Paul Bunyan tall tales. His sculptures and installations around the Wisconsin Concrete Park reflect this grandeur, showcasing his unique vision and dedication to his craft.

He didn’t set out with a grand plan to create 237 life-size and larger-than-life sculptures over fifteen working seasons. The project spanned 15 years, but the outdoor working conditions limited his ability to sculpt to a few short months each year. Like many artists, Fred Smith's work evolved from a deep love of craftsmanship and creativity. He crafted sculptures that honored Native American Indians, regional settlers, local myths, legends, figures, animals, and events of both national and personal significance.

In his own words, Smith once remarked, "Nobody knows why I made them, not even me. This work just came to me naturally. I started one day in 1948 and have been making a few sculptures a year ever since." He would eventually call this roadside attraction the Wisconsin Concrete Park.

Taking on this monumental project demanded immense time and effort from Smith. As he immersed himself deeper into his artistic endeavors, he began to withdraw from his family, focusing intensely on his sculptures. This familiar struggle between artistic dedication and domestic responsibilities echoed in Smith's life, a conflict shared by many artists.

Despite facing criticism and misunderstanding from those around him, Smith remained steadfast in his commitment to his art. He recognized its profound importance and continued to pour his creativity into the Wisconsin Concrete Park, steadfast in his vision of creating something extraordinary.

He took great delight in sharing his sculptures with visitors and cherished their interest in his work. Despite receiving admiration from some locals, many viewed Smith with skepticism, considering his park an eyesore that they hoped would disappear. Yet, Smith remained steadfast in his belief in the importance of his art.

He believed it was essential for people to view his work, but to view it exactly where it was. In 1974, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis approached Smith to feature his works in their Naives and Visionaries exhibition, the first of its kind to highlight self-taught environment builders. However, Smith declined the offer. He insisted that his art already was in a museum, it was a museum. Out of all the sculptures he created, Fred Smith made only one exception: a deer sculpture that he crafted for a friend. He steadfastly refused to sell any of his artworks or accept commissions.

"I welcome visitors," he once remarked. "I enjoy watching their reactions. But I never sell anything because it might spoil the experience for others."

In 1964, shortly after completing the last horse in his Budweiser Display, which we will circle back to, Fred Smith suffered a stroke. He was subsequently moved to a nursing home in Phillips, not far from the Wisconsin Concrete Park.

For the remaining eleven years of his life, Smith resided in the nursing home, where he continued to dream of sculptures he could no longer physically create. He passed away on February 21, 1976, and was laid to rest beside his wife Alta in Lakeside Cemetery in Phillips. Even today, friends and admirers visit his grave, leaving tokens of admiration and respect.

The creation of the Concrete Park

By the time Fred retired from his life as a lumberjack in 1948, he had accumulated 62 years of life experience and a reservoir of thoughts and ideas ready to be brought to life. His fascination with rock gardens initially manifested in the Rock Garden Room within his house, expanded into the outdoor Rock Garden as mentioned earlier, and culminated in the creation of the Rock Garden Tavern.

Around the parking area, Fred painted signs and dancing girls on boulders, and he even transformed a large, flat rock into a concrete sculpture resembling a seated Native American woman wrapped in a blanket. This marked the beginning of Fred Smith's artistic journey at the Wisconsin Concrete Park, where he unleashed his intuition.

According to legend, Smith built a grand stone barbecue adorned with concrete portraits of Native Americans to commemorate the baseball teams, the Indians and the Braves, who played in the Pennant—the precursor to the World Series—that year. He then created two double-sided deer plaques in the area where his rock garden once stood, situated between the Smith house and the Tavern.

These sculptures were initially built lying flat on the ground and later raised upright using a truck and a few helping hands. Smith's friend and neighbor, Leonard Lowe, who ran a salvage business, assisted in assembling and standing many of the sculptures. Lowe also sourced various “horse parts,” harnesses, carriage components, and other objects for Smith's creations.

Smith's primary material was concrete, which he adorned in various creative ways. His early works featured painted scenes and low-relief glass embellishments. As his art evolved, he decorated surfaces with glass, auto reflectors, mirrors, and other objects. He even recycled glass bottles from the tavern to add unique touches to his sculptures. Smith worked quickly and efficiently, understanding the nuances of his materials and learning to build sculptures from the ground up. Around the tavern, he created grand, two-sided sculptures of the Statue of Liberty and the Statue of Freedom on the Capitol Dome, showcasing his artistic vision and ingenuity.

He once described his process of making one of the sculptures:

First I make a footing about one-foot deep and pour concrete in it. The figures are started with a couple of strips of lumber which I wrap with mink or barbed wire. The arms and hands are made separately. After the form is made I begin filling it in with cement. I do half of it lying down, and then I raise it on the footing and do the remainder after it is standing up. Then the head, arms, and hands are erected to the form. It is then dressed with colored glass and other bits of things.

The Wisconsin Concrete Park boasts over 200 statues, so I won't cover them all here. To fully appreciate the breadth of Fred Smith's work, you should visit the park yourself or explore the extensive gallery on their website.

Smith sculpted a vast array of subjects, paying homage to various figures and events. He honored Chinese statesman Sun Yat-sen, Sacajawea—the Native American guide on the Lewis and Clark expedition—and created a monument to the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. His skills grew as he built two-dimensional works around the Tavern. North of the Smith House, his inspirations shifted toward recording local history, legends, and ways of life, adding a rich historical dimension to his creative endeavors.

Smith populated the park with an impressive array of ninety-nine animal sculptures. These include wild creatures like moose, elk, deer, panthers, skunks, and bears; domestic animals such as horses, oxen, cows, and hounds; and birds like eagles, ducks, and owls. He even crafted exotic animals, including a lion, tiger, and Angora cat.

The tiger statue is quite unique, and its inspiration came from a copy of They Taught Themselves by Sidney Janis. The book featured illustrations of paintings by Morris Hirshfield, a Brooklyn artist, including Angora Cat, Lion, and Tiger. Fred received this book from Chicago artist Robert Amft, who discovered the park while on a Northwoods fishing trip in the 1950s. Amft and Fred became friends, with Amft extensively photographing the park over the years. During one of his visits, Amft brought Smith a copy of the book. Months later, Amft returned to the site, and Smith proudly showed him his newly created sculptures, saying something like, "See, I can do just as good as that guy."

Smith also represented the first people to occupy the region, the Ojibwe, or Anishinaabe. One notable piece, the Indian and Woman tableau, depicts the ratification of a treaty with a local tribe, which Smith may have recalled from childhood. The scene shows a handshake between a Native American and a white woman, sealing the pact. The Native American figure, adorned with a stunning headdress and a clam-shell-encrusted garment, towers over the female figure, standing nearly twice her size. Smith used this difference in scale to emphasize the stature of the figures involved, or perhaps to symbolize the respect and admiration he held for Native Americans. Or rather that Natives where people to ‘look up to’, hence the statue looming over the white woman.

Smith had a deep fondness for Native American people and was deeply affected by the harsh treatment and efforts to drive them from their lands during the early 1900s. His strong feelings about the tension and inequality between whites and Native Americans were evident during an interview with Stephen Beal and Jim Zanzi in 1975. "I hear so much about Indians it makes me pretty near cry," he said, actually shedding tears. "Not far from here they want to run the Indians off. Indians don’t hurt nobody. They got the right anyway. They was the first people here, and they want to run them out now. Makes me crazy when I think of that kind of world. If there was no law, I believe they would shoot all the Indians down."

In the all-male lumber camps where Smith worked in his younger years, relating Paul Bunyan stories was a high-performance art. Reality and legend often blended together in these tales. Inspired by these stories, Smith depicted three local lumberjacks—Mr. Knox, Barry Swanson, and Gust Johnson—as colleagues of Paul Bunyan.

When Smith decided to build a statue of Paul Bunyan, the idea sparked a wager at the Rock Garden Tavern. Someone bet that Smith couldn’t make a statue of Paul Bunyan standing on a marble. Game on! Smith took the challenge and created a 16-foot tall statue of Bunyan, who bears a strong resemblance to Teddy Roosevelt, complete with wire-rim glasses and a rifle. And yes, Bunyan stands triumphantly on a large hemisphere—a marble.

Smith also created sculptures that depicted daily life, capturing people in everyday moments: sweethearts sitting on a rock, two couples in their Double Wedding carriage, a bandstand of musicians, a photographer, "Chiann" (Cheyanne) the cowboy beer drinker, and a sour-faced couple in a sleigh.

One of my personal favorites is Muskie Pulled by Horses, inspired by tavern talk. Claiming he had caught the biggest Muskie, Smith said his catch was so large it had to be pulled out of Soo Lake by a team of horses. As you know, fishermen never lie, so this must be a to-scale monument of the fish.

Finally, returning to The Budweiser Clydesdale Team, featuring eight draft horses and two ponies, originally included two figures and a dog seated on the wagon. While the figures are no longer intact, the dog now sits proudly at the head of the team. Smith positioned the Budweiser Clydesdale Team directly south of his Rock Garden Tavern. Shortly after completing the last horse in this iconic display, Smith suffered a stroke, marking the end of an era. This monument would be his final project.

Approaching from the south on Highway 13, spectators had reason to gasp and pull over. The Budweiser Clydesdale Team signaled something extraordinary in the northwoods – and it wasn’t just beer.

Then what happened: The Wisconsin Concrete Park, 1976 – 1987

Fortunately, Fred Smith’s Wisconsin Concrete Park outlived its creator. In 1976, the site, excluding the tavern and its immediate surroundings, was acquired by the Kohler Foundation, Inc. of Kohler, WI. A restoration project commenced in the spring of 1977.

Since the tavern was not part of the Kohler Foundation's acquisition, all but one sculpture on the tavern property were relocated and reinstalled in the present east meadow. The owner of the Rock Garden Tavern insisted that the Iwo Jima monument remain. Artists Don Howlett and Sharron Quasius were enlisted to relocate and repair sculptures, and prepare the site to become a Price County Park.

Don and Sharron were well into the project when a devastating cyclonic downburst struck Price County, wreaking havoc on the park. Numerous mature trees, essential to the park's landscape, were toppled, necessitating extensive restoration efforts. The site had to be cleared of debris, with many sculptures requiring repairs and new concrete footings.

After months of dedicated restoration work, the project was completed in September 1978. Subsequently, Kohler Foundation, Inc., generously gifted the site to Price County as a county park and museum.

During the summer of 1987, a site conservation and maintenance project was underway at the park. On July 4th, exactly ten years after the initial windstorm, a second storm struck the area, causing further damage to the sculptures and landscape. Whether coincidence or curse, the park persevered.

Following the repair of storm damage, an annual maintenance program was established. Today, ongoing preservation efforts focus on maintaining the sculptures, house, and landscape as integral parts of the park's historical context, reflecting Fred Smith's artistic vision during his active years from 1948 to 1964.

Founded in 1995, the Friends of Fred Smith, Inc. is dedicated to supporting the Wisconsin Concrete Park in collaboration with Price County. Their mission, as stated on their website, is clear: to preserve all aspects of the Wisconsin Concrete Park, including its sculptures, landscape, and the historic Smith Family House. Their goal is not only preservation but also the ongoing development of the park as a public educational and cultural facility.

With a vision to enrich the community through cultural, historical, and artistic resources, the Friends of Fred Smith, Inc. aims to expand individual potential and foster unity among people. Today, the park continues to be maintained by a dedicated board of directors, which includes some of its founding members. Additionally, the park features buildings available for community events and private parties, further enhancing its role as a vibrant community asset.

After acquiring the former Stoney Pub, the Friends of Fred Smith made a crucial decision to purchase the property, aiming to preserve its historic significance and enhance community engagement with the park. Following extensive renovations and restorations, the tavern reopened its doors to the public in 2019. Visitors can now enjoy a selection of beverages including Rhinelander beer, a favorite of Fred Smith's, alongside hard sodas, mixed drinks, a diverse wine collection, and soft drinks. Operating hours are Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays from 3 to 9 p.m.

The upper level of the tavern has been transformed into a charming two-bedroom apartment available for rent on Airbnb. All proceeds generated from both the tavern and apartment rentals contribute directly to the ongoing preservation efforts of the park. This initiative ensures that Fred Smith's vision of an accessible, open-air art museum remains alive and thriving for future generations to experience and enjoy.

Haunted park?

The Wisconsin Concrete Park welcomes visitors year-round, offering unrestricted access 24/7. During the summer months, complimentary tours are available every Friday at 2 pm, providing an informative glimpse into the park's rich history and artistic legacy.

Exploring during daylight reveals picturesque trails like the Budweiser Trail, which I personally hiked. This easy loop trail winds around the park's scenic backdrops, inviting peaceful strolls amidst nature's beauty.

However, visiting after sunset introduces a different atmosphere. Locals and visitors have long considered the park haunted, a notion even chronicled in Chad Lewis and Terry Fisk's book, "The Wisconsin Road Guide to Haunted Places," despite some inaccuracies in its historical accounts. Reports of statues seemingly moving on their own and sightings of ghostly figures add to the park's eerie reputation. Mysterious noises and strange occurrences have been part of local lore since the 1970s, often attributed to the restless spirit of Fred Smith himself or other unexplained entities.

During my visit in broad daylight, I didn't encounter anything supernatural. Yet, the park's unique ambiance and the lifelike sculptures can evoke an uncanny feeling, as if being observed. Whether the park is truly haunted remains open to personal interpretation, but its distinctive charm and artistic allure are undeniable, making it a must-visit destination for curious adventurers.

Whether you come to marvel at the artistry, immerse yourself in local history, or simply enjoy a peaceful hike along the Budweiser Trail, the Wisconsin Concrete Park invites you to form your own impressions. It's a place where the ordinary transforms into the extraordinary, offering a unique glimpse into the creative spirit and enduring legacy of Fred Smith.

So, the next time you're in the area, pause for a moment of discovery at this captivating and unconventional destination. Whether you seek artistic inspiration, a touch of local folklore, or simply a memorable adventure, the Wisconsin Concrete Park promises an experience that's as enriching as it is unforgettable.